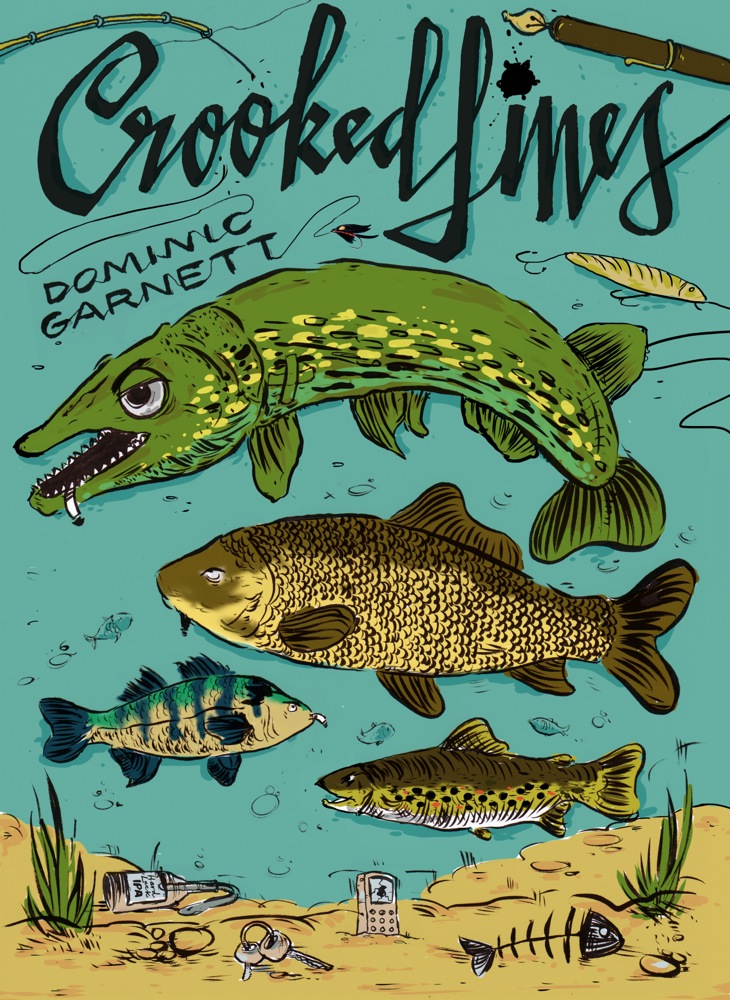

Dominic Garnett

No matter how many times I pack a suitcase or study the guide, fishing trips in far off places always sidestep expectations. From the picture you build in your head to the flies and even the weather, something different always hatches. Things mutate. Sometimes you expect easy listening but you get punk rock.

Which is funny, because rather than some grand Irish River, this particular trip begins in a second hand car in Tipperary. I hadn’t been to Ireland for a good eight years, but the one picture I found reliably true to life was my host, Aidan Curran. A red-mohicanned punk with a taste for fly fishing.

“I guess I’m not your typical game angler,” he chuckles, as the car rattles with loud music. No word of a lie. The bands we are listening to have names like Sick Pig, Crisis and Runnin’ Riot. “Pike fishing is definitely something that appeals to punks, but trout or fly fishing? It’s not such an obvious match is it? People think you’re pulling their leg.”

Aiden’s dented car takes innumerable turns down crooked country lanes as we seek out the river. But behind his wild appearance is the subtler, laid back heart of an angler. In his own unique way, Aidan is just the next in a long line of colourful River Suir regulars, or should I say irregulars. Perhaps the greatest of them all was Liamy Farrell, described so beautifully in the writing of Niall Fallon as a “rotund, stocky” bull of a man with “rolling, limping walk.” Yet in spite of his burly frame and a rod that could have landed sharks, this grizzled character could make his fly land “like the kiss of an angel.”

A refreshingly frank Suir angler from the present day is guide George McGrath, who meets us in stately looking grounds by the Ara, a pretty little tributary of the Suir. “Are you any good with a fly rod?” he asks, only half teasing. “Because if yer shite you won’t be ketching much round here.” With a slightly despairing shake of the head, George recalls an American guest with a PHD in entomology. A nice enough bloke with all the right gear who sadly couldn’t hit the Rock of Cashel at ten paces.

Quality water is abundant here and in fact the Suir and its’ tributaries offer the highest density of trout of any river in Ireland and quite possibly Europe. But that doesn’t mean “easy” fishing, as George will testify. And he’s fished these waters for so many years I’m wondering if his folks had a fly patch sewn onto his babygrow.

Lesson number one is in fly selection. The typical advice for Ireland is so often of the “big flies for big fish” variety and yet a peek at George’s box reveals a good deal of specials in the size 16 bracket, with both little olives and sedges prominent. I need no second invitation to poach a few of these.

Lesson two, about the legendary fussiness of local trout, is dispensed in the field as Aiden and I hop onto the Ara for an initial foray. It looks beautiful in the sun. Shallow waters reveal trout by the dozen. They multiply before your eyes and are everywhere, flitting over the pale, sandy bottom of the river. You feel like you’ve stumbled upon paradise until you actually try casting for these little devils, which are among the spookiest trout I’ve ever come across in my entire sorry existence.

For the first two hours we try everything: long, fine leaders; tiny flies; longer casts. It’s simply bordering on impossible to tempt these fish, or more precisely to get near them without raising panic. When I’d previously heard Aidan’s missives about the shyness of the fish I had joked about him getting his hair dyed green instead of bright red. I now believe you’d need to be a camouflaged midget, invisible or able to levitate rather than wade to get anywhere near the buggers. It is pure agony to see such riches slip away at every bend in the stream.

Nevertheless, revenge is almost served as we have one final crack in a bigger bridge pool where a few more sizeable fish are lying and, touch wood, with more water to cover them don’t seem quite so desperately spooky. With George joining Aidan on the bridge I now have two extra pairs of watchful eyes -and extra pressure!- to try and end a frustrating afternoon on a happy note.

“A little further upstream” or “Just in that hole, there!” come the regular words of advice. I can make out some shapes that are way bigger than the little runts we spooked earlier, but will they show any interest? The moment of truth comes as I manage to drop a heavy nymph so it passes right above a tempting little depression on the stream bed; a dark shape shifts across the current, there is a decisive flash and all hell breaks loose. For about five seconds the rod bends dangerously as I pay out line; next there is just slackness and a lone swearword. George’s next declaration has already been ringing through my head: “He won’t be coming back any time soon now.”

With a week of sultry-hot, distinctly un-Irish weather ahead, most of our fishing the next two days takes place in conversations over coffee or beer. Trips to pretty local towns and crumbling relics appease our curiosity and also our womenfolk while we plot our next assault on the Suir.

The area is full of spectacular ruins that, if they were in England, would be continually assaulted by coach loads of invading pensioners. But here everything is peacefully vacant. I admit to finding this slowly rusting side of Ireland reassuring. Samuel Beckett must have agreed when he wrote that: “What constitutes the charm of our country, apart from its scant population, and this without help of the meanest contraceptive, is that all is derelict.”

The bones of old castles sit splendidly idle, daisies growing from their windows. Such are the torn remains of what looks like a medieval turret sitting by the Suir just outside Cashel. The waters are sparkling and, as is always the case when you don’t have a fishing rod, we spot trout moving in the stony runs and rushing water.

An evening return is plotted, but until that time we must be content ourselves with fishing trips made in books. Among all the advice on Irish trout fishing are the accounts of night fishing such as those from Niall Fallon’s “Fly Fishing on Irish Rivers” are especially bewitching. On a hot summers day this can be the only time Suir trout really drop their guard. The reasons involve science as well as alchemy; “Invertebrate drift” is the term used to describe the nightly emergence of life forms on the river. During the witching hours, all that was hidden ventures out. An endless collection of creatures crawl from their hiding places in river bed. The trout suddenly find their appetite and grow bolder.

This was also the favourite time of Liamy Farrell, who could be observed immersing his stocky frame into the river while more timid souls packed up for the evening. “Where others were glad to climb out of the strong waters of the Suir with an acceptable brace of trout on a July evening, Liamy would meet you on the bank in the warm, scented dusk with half a dozen, topped by a three-pounder” writes Fallon. “He liked to get right in amongst a shoal of feeding trout, moving with the utmost patience and slowness, and fish a very short line either side and above,”

The first hour or two on our return to the Suir near Cashel begin with a friend of a friend and a rusty gate. The river drops away invitingly at the end of lush fields, but the only signs of life are odd rises well out into the current. Long leaders and distance casts earn only the most occasional of finicky takes until the light begins to drop. Aidan aims a team of traditional wet flies across the current to mix things up, but one hit and miss take is all our river punk can muster so far. Once again, we’re foxed.

It is only as the light drops that the rises become more frequent and we spot a familiar, tall figure working the far bank. It is George, here to teach us a lesson presumably. Creeping along up to his thighs he searches the stony shallows with quick, short casts. Within minutes his rod jolts over and a Suir trout is kicking at his side. Aiden and I stand watching in that semi-appreciative way unsuccessful fishermen do in the presence of a local expert. Another trout comes to hand. And another the very next cast. “Just watch the bugger! You have to admit, he knows a trick or three though.”

Hoping that the dying light will help to conceal my own lanky presence, I double back along the bank and drop into another shallow run, the water just about covering my knees. Where there was only a cool flow of water minutes earlier, there are now regular, splashy rises. As if someone had flicked a switch.

Tying on a small Balloon Caddis, I flick the fly into the stony run and pick up the line gingerly. I lose sight of the fly, but there is a sudden rush at the surface and I’m attached to a lively half pounder.

Quite soon you can hardly make out the fly, but it hardly seems to matter. Numbers two and three follow, while the whole river seems to buzz into life. I throw a couple of painfully clumsy casts along with the better ones; the trout seem oblivious. At one stage they’re rising directly just a couple of rod lengths behind me, totally untroubled.

Such is this magical time on the Suir that in the space of half an hour a frustrated amateur can be transformed into a trout fishing assassin. The change is so dramatic you wonder how you ever found it so difficult beforehand, but it’s an exhilarating feeling. The fish don’t sip, they smash. The best of them probably wouldn’t quite trouble the pound mark, but kicks and thrashes as hard as a punk rock band.

Tipperary is sleeping as we return home quite a lot later than planned, leaving the Suir to the trout and Liamy Farrell’s ghost. Moths swarm down the overgrown lanes to Aidan’s place as we gather in the night sky, still damp from the river. The best trout tastes beautiful, freshly fried in butter by the river punk himself.